Part of learning about my family history has focused on learning the counties and towns/cities where past generations lived. My grandmother told me the earliest stories of places, but I couldn’t get a grasp beyond Savannah,GA and Hilton Head, SC: the two locations I remember the most when visiting my grandmother. On trips to Savannah, she would say she needed to take me to “Harris Neck” to show me her grandfather’s land. Anyone who has been to the Low Country of Georgia and South Carolina knows that these lands can appear identical in topography and culture: Live Oaks with streaming strands of “moss,” historical markers for the few existing structures from early Georgia, and rising and ebbing tides inland or at the beach. It’s deceptive on the surface, but each area is quite distinct beyond the allure of the natural environs.

The land has as many stories to tell as its inhabitants. While traveling to an area, and enjoying Nature’s rich bounty, I remind myself of the mixed threads of yarn that make up the fabric of an area’s narratives. Southern histories are particularly problematic; some are grounded in the great oral traditions and songs of our forebearers, some are recorded in documents without explanation, and some are myths from the beginning, unfolding like heels dug in the sand, waiting for the tides to wash away their footprints. I realize our stories are tender, dear, and unsettling all in one moment.

LAND is at the center of it all. It is the center of so many ongoing wars and disputes today in any part of any country in the world. Isn’t it also the place where we gather to console one another or share a memory of once when we were in a place and time together, all associated with the land we knew, or thought we knew? We traverse the land, we tell stories about the land, we buy and sell land, we travel to distant lands, and we remember lands we never knew, but like DNA markers, they pull at us. I’m reminded of Robert Frost’s poem “Mending Wall” when the speaker says “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall” as he and his neighbor mend a stone wall that the land has toppled each season, naturally, in resistance to the constraints placed on the earth. The act of mending the wall together is a ritual, but their feelings toward the mending are not the same: one neighbor feels stuck on an adage of his father, “Good fences make good neighbors” while the other ruminates, “Before I built a wall I’d ask to know/What I was walling in or walling out,/And to whom I was like to give offense.” I think of landscape photography, where from a distance, we view a patchwork quilt of farms or properties, all divided up, evidence of humans charting their territory and warning others to stay on their portions. But we all know, the land is a contiguous space, and we are only here on it for a short period of time in the grand scheme of things. LAND is at the center of it all.

When I started this project, I used my great-great-grandfather’s memoir as a guide to locations. And for the past two years, I have traveled to these locations trying to piece together all the family names to their movements. This blog post is an attempt to give a sense of the main areas in Georgia where I have followed the Thomas family and the families into which they married. Broadly speaking, my family comes from the Coastal Regions of Georgia and South Carolina, with another location in South Carolina near Limestone Springs. However, siblings and others in the family have ventured to multiple locations across the United States.

On a recent road trip to St. Louis, MO, I passed a sign in Tennessee that said “Tullahoma.” I wondered why I knew that name for a town I had never visited or heard of. Then a pair of death certificates belonging to two Curtis sisters registered in my memory. They had died in Coffee County, Tullahoma, TN in 1928 and 1929 respectively. One of them had married the oldest son of the Thomas family (my great-great-grandfather’s brother John Huguenin Thomas, JHT), but he died in 1873, barely married to Eliza “Lila” Amanda Curtis that same year; she is both my aunt and cousin by marriage as she is my great-great-grandmother’s niece (her oldest sister’s daughter). On my way back from Missouri, I decided I would have to go to Tullahoma, even if it was for a 5-minute walk, hoping to get a sense of why these two women would have ended up in this location. The railroad in the middle of the town gave me a reason, which I’ll get to another time. The point is that I have traveled to all kinds of spots in the Southeast to get a sense of place.

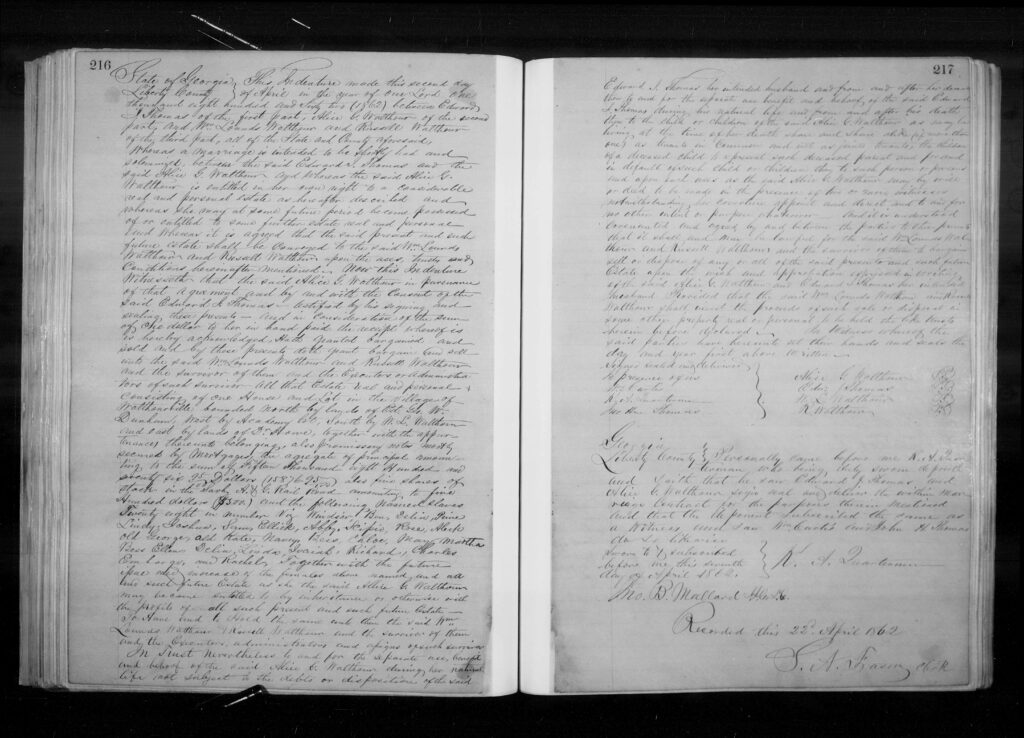

Before the Civil War as early as the late 1700s, the Thomas family was one of the largest landowners in McIntosh County, GA, and my great-great-grandfather (Edward Jonathan Thomas, EJT) married my great-great-grandmother (Alice Gertrude Walthour, AGW) whose family was the largest landowning family of Liberty County, GA. The fathers of both my second great-grandparents had died by 1859, leaving these huge estates to their wives and children. When the Thomas family married the Walthour family, it was a merger of great wealth and land ownership. It also meant that the people held in bondage by these families would be part of the marriage settlement of EJT and AGW.

The marriages of the Thomas patriarchs, in particular, resulted in land acquisition and an increase in the number of people they enslaved. Every time I visit a place, I am ever mindful of these facts. Some of us can trace our ancestors’ movements across lands by investigating deeds, wills, and other items; many Americans, especially those with ancestors held in bondage, have a much more difficult task of finding their roots.

Using Edward Jonathan Thomas’s (EJT’s) memoirs as the anchor for understanding where my ancestors lived, here are the major locations in Georgia I have visited:

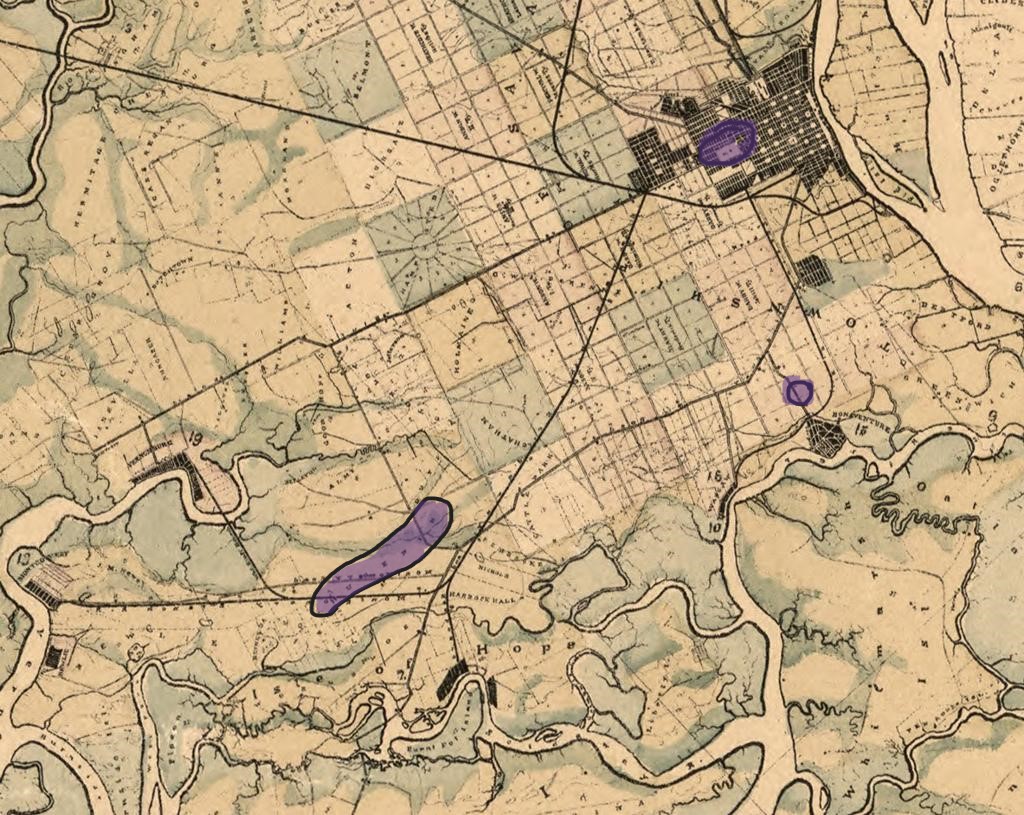

Purple areas indicate City of Savannah (above), EJ Thomas farm (circle right), and Hugenin [sic] Land (left)

- Chatham County, Savannah, GA and vicinity

Edward Jonathan Thomas was born in Savannah, GA in 1840 on Broughton two houses down from Habersham on the south side of the street, and he lived there with his father John Abbott Thomas (JAT) and mother Eliza Henrietta Huguenin (EHH) for a few years. His father was the Deputy Port Collector in Savannah, and his brother JHT was born a year earlier. A sister, Eliza Huguenin Thomas (EHT) would be born in 1842. EHH was the daughter of John Huguenin (JH) and Eliza Vallard Huguenin (EVH), and she was one of three children. John Huguenin came from Charleston and bought a large swath of land south of Savannah, GA in 1825 where he had a very large plantation of approximately 1,400 acres above the Isle of Hope. That land in the years after the Civil War would revert to the Thomas family after the death of EVH in 1870. Savannah will be the center of the Thomas family post-Civil War, primarily as a result of selling land in McIntosh County and Huguenin land in the Savannah, GA vicinity. By the 1900s, my great-great-grandparents would be in the city of Savannah (Liberty Street, McDonough Street, Abercorn, and E. Oglethorpe Street) and also operate a farm just outside the gates of Bonaventure Cemetery. The three major areas where my ancestors lived are highlighted on the map above in purple.

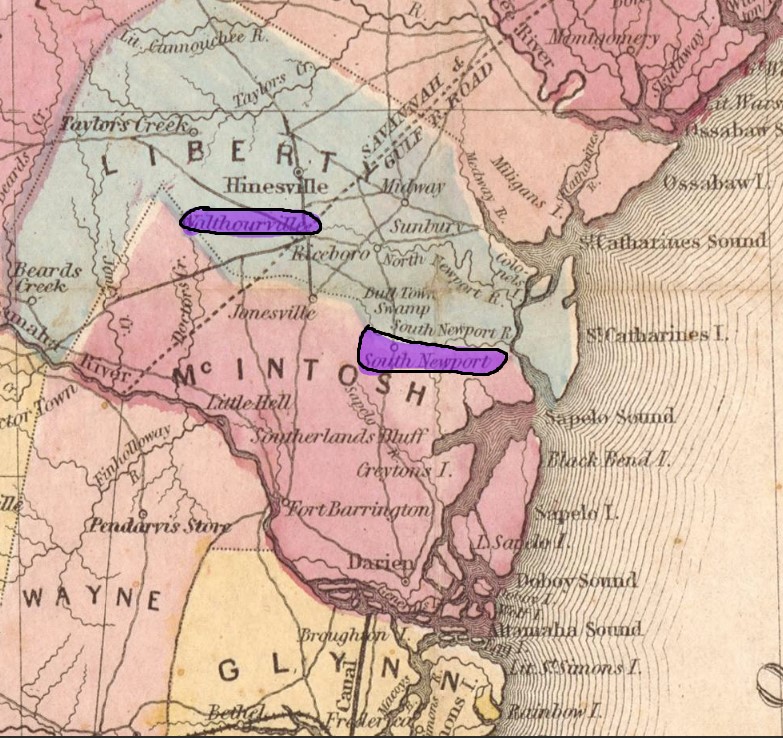

- McIntosh and Liberty Counties, GA

John Abbott Thomas’s father, Major Jonathan Thomas (JT), was located primarily in McIntosh County where he was married to his second wife Mary Ann Houstoun (born Williamson), a widow of James Houstoun with children of her own. The Houstoun family papers in the Georgia Historical Society provide a thorough history of that family’s political, economic, and land acquisition for many years. In McIntosh County, due to marriages (his first being to a Mary Jane Baker whose family held much of the land surrounding Harris Neck) and land acquisitions of his own, JT was able to garner about 15,000 acres of land, all along the South Newport River in tracts called Peru, Stark, Lowe, Eagle Neck, Mosquito, and Marengo (today, tracts of land from Hwy 17 to the area now called the U. S. Fish & Wildlife Harris Neck Refuge).

JT’s father and arrival in McIntosh County are still a mystery for me, but according to EJT’s memoir, we descend from a “Captain John Thomas,” the captain of the ship that brought James Oglethorpe and the original Georgia colonists in 1732. I can’t establish the verity of the story of our ancestor, but the ship Anne does list such a captain. Between 1732 and about 1800, how our Thomas family ended up in McIntosh is still part of my investigations.

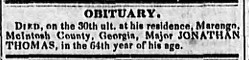

In 1835, John Abbott Thomas graduated from Franklin College (UGA now). In 1838, he married Malvina Henrietta Huguenin. Before the death of Major Jonathan Thomas in 1845, and after his son was removed from his Deputy Collector position in Savannah, John Abbott Thomas moved his family from Savannah to Peru Plantation in Harris Neck, McIntosh County. The family is listed in the 1850 Census of McIntosh County, District 22 with five of their children. There, he and Malvina Henrietta had seven or eight children in total: John Huguenin Thomas, Edward Jonathan Thomas, Eliza Huguenin Thomas, Mary Jane Thomas, Malvina Huguenin Thomas, Jr., Matty King Thomas, Marion Thomas (female), and Houstoun Huguenin Thomas. Marion Thomas would die very early in life, and she is barely found in records except for the fact that she is listed in some early church records in neighboring Liberty County—it is possible that Marion is actually Houstoun Huguenin Thomas, but for now, I’m keeping that separate. JAT lived at Peru Plantation and JAT’s father JT would live on a plantation called Marengo on the other end of Peru until his death in 1845 at Marengo. His death at Marengo has only just been recently found (thanks to reading Harris Neck & Its Environs: Land Use & Landscape in North McIntosh County, Georgia by Buddy Sullivan, a writer who has documented McIntosh County history for many years). This book helped me put in “Marengo” as a search term instead of “Harris Neck,” and Major Jonathan Thomas’s singular death notice can be found in the Savannah papers in 1845. This small piece of information has taken me two years to locate. Until now, people have assumed Jonathan Thomas died closer to 1849 because he was in the McIntosh Censuses before 1850.

John Abbott Thomas (JT’s son) would inherit many of the lands along with Major Jonathan Thomas’s widow. From 1845, JAT would be the head of the household until his untimely death in 1859 after being thrown from a buggy that his son EJT was in. JAT suffered a brain injury that he never recovered from. It’s important to note that during 1856-1860, both JAT’s oldest sons (John and Edward) were attending college at UGA, so their family was headed by their mother, an executor (neighboring William J. King), and hired overseers on the properties when JAT dies in 1859. Their two oldest sisters, Eliza and Mary Jane, would also be sent away to boarding schools after the death of their father—one in Montpelier, GA, and the other in Philadelphia, PA. I mention this because if one reads my great-great grandfather’s memoir called Memoirs of a Southerner, one might believe that after his father’s death, he came directly home and set about being the “Master” of the land; however, EJT was not in a hurry to come home from his graduation as his mother had arranged for the estate executor to hire someone to act in charge of the plantation and its inhabitants (by EJT’s estimate, about 125 enslaved people). I know some of these new details about this time from a very recent and exciting discovery in the Georgia Historical Society: the memoir that I reference in this blog, the one published and easily available online, is the edited version of a memoir he wrote in 1890, only on microfilm as part of the Mrs. Ralph V. Wood collection on prominent Georgians (GHS 1614). I will use another post to discuss the memoirs, plural, but I’m including these new details because it reminds me to reread both memoirs to eke out any new details to the narratives of my ancestors (the new one is barely legible on microfilm, so it is slow going).

While McIntosh County held much of the land of the Thomases, the family resided in both McIntosh and Liberty Counties between 1850 and 1860 because Liberty had schools for the younger children. According to EJT’s memoirs, their home in Walthourville was near the home of George Washington Walthour (son of Andrew Walthour, the founder of Walthourville, before called Sand Hills) and Mary Ann Amelia Russell, Alice Gertrude Walthour’s parents. That connection and proximity to the two families would bind the counties together as neighbors, then as married families when Alice and Edward married in 1862, after their fathers’ deaths in 1859. The economic advantages of the Walthour family were so great that when the Thomas family married into the Walthour family, the expansive nature of the economic growth and power would be the financial security for generations to come (George Washington Walthour was the largest landowner of Liberty County with three plantations called Homestead, Richland, and Westfield, with approximately 300 enslaved people listed on his estate inventory after his death).

Bonner, William G. Bonner’s pocket map of the state of Georgia. New York: J.H. Colton & Co, 1854. Map.

Retrieved from the Library of Congress

I’m still working on the documents of Liberty County and tracing our family roots, but a great resource for people learning about Liberty County is They Had Names by Stacy Ashmore Cole. Cole’s work is an incredible resource that identifies the descendants of people enslaved in Liberty County and their enslavers with a treasure trove of documentation (wills, deeds, marriage contracts, indentures, Southern Claims Commission documents, promissory notes, Freedmen Bureau records, and more). It also serves as instruction for anyone who is doing family history research using Family Search, which is free to use, and it’s the place where I started my online inquiries. By typing in “Walthour” as a search on They Had Names, I can see approximately 35 pages of documentation Cole has provided on the site for anyone with that name.

This is a dense post, I know. This is just the toe-dip in the sands of my travels, but it gives a sense of locations as they are mentioned in my great-great-grandfather’s memoirs and my research at various institutions. If I hadn’t gone to Savannah, GA in 2024 for a month of research, I might have missed discovering the Huguenin land in Chatham County and how the Thomases came to inherit it. I spent hours in the Georgia Historical Society making fruitless searches for days, but one day, I was able to find that a search of “John Huguenin” indicated there was a folder (singular) in the WPA (Work Projects Administration) Georgia Writer’s Project (MS 1355) regarding property in “Bethesda.” The entire collection is 39 boxes for the Savannah Unit alone, and it is unpublished. I was expecting it to maybe yield one document; however, once I opened up the folder, I saw file after file of land sales and exchanges (all transcribed) for the entire Thomas family from the early 1880s well into the 1900s, not so much on John Huguenin. I decided I would look at all the folders in multiple boxes of Bethesda (the project is divided by territory–so if you don’t know the territory or the name of a particular (White male) ancestor, you might as well be looking for a needle in a haystack). It yielded so many more documents. It unsettled me that the only access point to the countless names and land exchanges relied on me knowing the name of a patriarch of my family (going back 4 generations). John Huguenin, my 4th great-grandfather, acquired the land in 1825 and died by 1835, leaving my 4th great-grandmother as the sole owner. Her daughter Malvina Henrietta Huguenin, along with her siblings, would inherit the land eventually. But as in all things related to land, those dispersions would encounter legal hurdles, jockeying among family members for their portions, and battling the executors and administrators of the estates. It also shows that the lands were sold to freedmen/women of different races, something that points out that indexes to archives are as archaic as the documents held within, buried in an institution where access is granted, but only if you know the solution to these two riddles: Who are your people? Where are they from?

The same would happen in McIntosh and Liberty Counties (and other places during the Civil War and after). The full Thomas family would own portions of this land, brothers and sisters, husbands/wives, grandchildren, and freedpeople via sales or deeds. All part of my ongoing research, initiated with the earliest mention by my grandmother of the land of Harris Neck. This once-foreign location of my imagination would come into view as a result of a conversation with my cousin who suggested I broaden an online search to “direct descendants of Harris Neck.” Then I made a phone call that changed my life.