Whenever I unbox a new gadget, I often ignore the operation manual. I usually fumble around, perform a bunch of unscripted tactics, and voila, I figure it out. Or not. Then, maybe, I pull out the instructions to witness the breadcrumbs of predictable mistakes I could have skipped had I considered the proper steps, all detailed in the manual.

I have learned the hard way that some things are not operation-ready at the moment of unboxing. In my photography ventures, I have cursed myself for trying to launch programs through the Adobe suite of tools to start editing photographs without consulting the book I bought about cataloging imports of images appropriately. I am an impatient person. Because I ignore the best advice (read the freaking instructions), I now have trouble locating my best photographs because of that eager adoption of chaos for immediate edited-image gratification.

I’ll be honest about this family history project of mine. I ignored my own best intentions. I moved items to my office, and I “made space for them.” I had adopted a method in my approach—one person at a time, one date at a time, one document/heirloom at a time. I was building a tree for the family to “know their history,” but the history of each item started to unravel in ways I had never fully anticipated or appreciated.

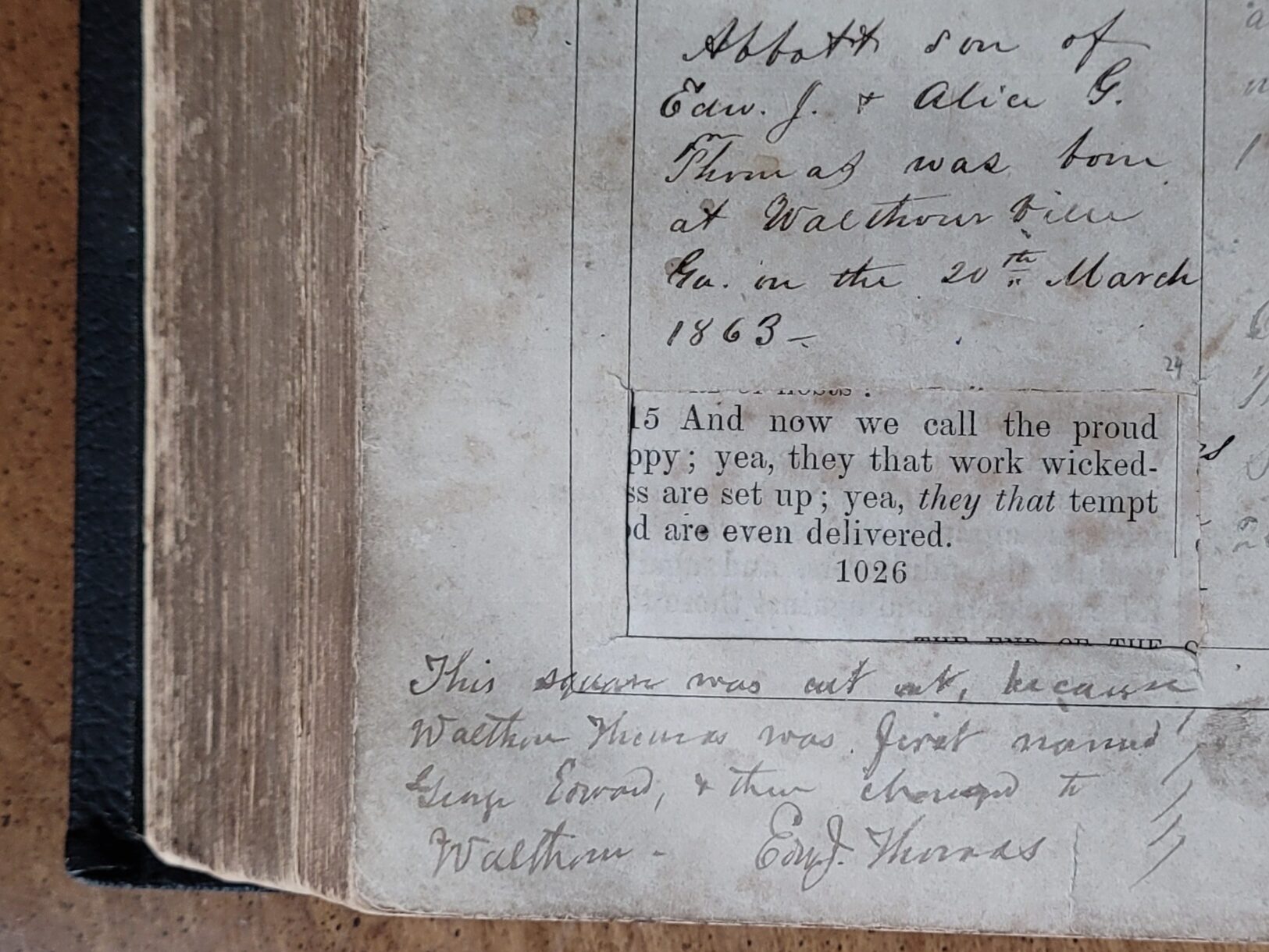

I knew that the family Bible was grounding—a list of births, deaths, and marriages written in ancient writing with some pasted news articles to accompany those events. There was even a square cut out because a child’s name was changed from the original entry, with an accompanying explanation of the cutout.

What I didn’t anticipate was a six-paged, handwritten speech to drop out and unveil from the pages when I opened the book. It was in cursive, in tender condition, and it had blotches of watermarks blurring certain lines (did it get caught in the rain, I wondered), but it was dated. At the top right of this speech is “Savannah Oct 27 – 1913, Reminiscences of Savannah” and to the left top is “Mr. Pres & Members of University Club of GA, Savannah.” This speech is written by Edward Jonathan Thomas (EJT), my great-great-grandfather, and grandfather to my grandmother Ethel Butler Thomas Hunter. EJT was a graduate of the University of Georgia in 1860, as was his older brother John Huguenin Thomas in the same year. And their father, John Joel Abbott Thomas, was a graduate of the University of Georgia (then Franklin College) in 1835. By the time of this speech, both his older brother and father would be dead. In 1913, EJT was 73 years old.

I scanned the document to prevent any further damage to it, and I started the long process of transcribing the speech. When I say that it was practically illegible, I am not joking. I made a Word document that started line by line, with each word I decoded in the exact location of the document. I entered “?” for any word I could not recognize. I repeated this process over and over with the question mark for any spot where I was stuck on a word. I would have to step away from the document to avoid being discouraged.

Sometimes, I make a silly challenge to anyone interested in this document: “I will give you $1,000 if you can transcribe this speech.” People take on the challenge gladly, and then they hit line one and say, “Woah, I can’t read this!” My money is safe with me. I haven’t met a seasoned writing expert who can tackle this speech yet.

Slowly, I came back to the document and worked to read the hand of my great-great-grandfather, assess his shorthand, and anticipate the certain letters that were nothing like any cursive writing I had witnessed (and here I thought my father’s letters to me in youth were difficult; this was a whole new chapter in decoding script). Eventually, the question marks became terms, and the terms would lead to pauses for online inquiries in case a name or a location could provide context to his speech.

After a year of honing my transcription skills, I am almost done with the speech, and the process by which I have arrived at the full rendering is the key to how I operate in family research.

Operating Instruction #1—you don’t know what you’ll find, but if you can interpret it, be ready for what you learn.

In the speech, I recognized my great-great-grandfather’s voice as that of his memoir copyrighted in 1912. Perhaps this was his promotion tour for Memoirs of a Southerner: 1840-1923 or perhaps he was crafting the memoir in these speeches as he was writing his reflections on his life. In some biographies of Edward Jonathan Thomas, he is noted for his habit of regaling audiences with his imaginative tales. This would be no different. He starts off, “You ask me to tell you about the people of our dear ole Sav’h [Savannah], way back yonder ‘before the war’, & before the recollection of any of those before me—I have always loved to chat with those I am in sympathy with, and it is only in a chatty mood I beg you now to talk anew tonight—& if by chance while chattering I become fantastic or even shocking, just attribute it to my youth, for you know I am speaking of the boys of long ago, & besides are we not to be all boys for tonight—.”

The speech is a full examination of his time in Savannah in youth, during the Civil War, after the war, and it is a veritable Who’s Who of Savannah from 1848 and later. I learned about the outbreak of “Yellow Fever” in 1854 and a storm that almost brought the city to ruin; the ill-conceived plantings of “china berries & mulberries” on the streets and squares or Savannah; the parading of the Volunteer guards (and competing regiments); the 1858 funeral procession of Dr. Richard Wayne with a funeral hymn sung by “negroes, in appreciation of their love & respect for him;” the recommendation for a monument for “our black friends;” the unveiling of the Palaski Monument; boyhood escapades wandering the streets of Savannah; the place he took dance lessons; a list of churches and their pastors; all the names of men in the different industries (banking, commerce, and railroad ) of Savannah; character sketches of people like Mr. Gaulidet “—a remarkable man of habits—to the minute each day he left his house walking down Bull St. & so regular was he that his neighbors set their watches by his coming & going—Always immaculately dressed—in summer white trousers so stiff & unbending that twas said he placed them between 2 chairs & jumped in them from above, that no crease would show.” Edward J. Thomas was in his element entertaining an audience of men, no doubt. And I would laugh at these references along with them.

And then he drops two more terms I had to look up: “sloop Wanderer” and “Ten-Broeck Racecourse.”

These were not terms with which I was familiar a year ago. Nor had they ever been brought up in any American History course of my youth, my undergraduate years, and not even my graduate courses (where I spent most of my time studying 19th-century and early 20th-century literature courses centered on African American autobiographies and the Harlem Renaissance).

I would learn that the Wanderer is the name of the ship that carried the single largest illegal shipment of enslaved people in 1858 after the practice had been outlawed in 1808. My great-great-grandfather seemed to dismiss the entire thing as a “Yankee enterprise.” It was carried out by Charley Lamar, the character in this speech who chased off a bull that took refuge in a garden, and who was the “self-appointed” police of the city. He also was one of the primary supporters of the Ten-Broeck Racecourse, which by 1857 was the site of the largest sale of over 400 humans in U.S. History (called the “Weeping Time”) by Pierce Butler to pay off his gambling debts. By the time of this speech, Charles Augustus Lafayette Lamar was well past being exonerated for his transgressions, and all that can be recalled in 1913 is that when taken to the racecourse as a lad, E. J. Thomas recounts that “Charley Lamar shot H. DuBignon’s eye out—good friends around a dinner table, but Champagne & a few unfortunate words made [Lamar] forget.”

The attempts at humor in this speech as it regarded Lamar pointed out something I feel I’ve recognized all my life—we sometimes sway our moral compass to allow for transgressions. History is not a settled enterprise by any means. This speech is just one tiny part of my personal education.

Operating Instruction #2—There is immense benefit in re-examining history. We aren’t rewriting history. We’re finally unearthing history.

I allow for uncomfortable moments to absorb into me—I don’t need to do a meticulous accounting of my ancestors’ faults—that would be passing on some kind of weird guilt track that has real harm value to others if I do. The speech is just one example of how I have accessed the life and times of my great-great-grandfather. Still, I also realize that two significant times in history are only now getting their full recognition in courses taught in American History (and they are still being left out). While it may be more recently that the events are coming to light in a book or online, we have known it all along whether we admit it or not. It’s been in our parlors, dining rooms, speech venues, politics, and everyday conversations.

My great-great-grandfather would have known then that these events, back-to-back in years, and back-to-back in their lawlessness defined his generation. And he embraced it still in 1913. With enough power, a man of his time could operate as he liked in society. His generation looked back in time, generating mythological tales that still register in the minds of generations that followed, and as a result, the truth sits squarely in front of me every time I open a document or start deciphering the items in my Family Vault.

We know what we know. We also know what we feel; I firmly believe that. As a young girl, I remember feeling the moment an awkwardness might appear in a conversation when I felt that what was being said was just “not right,” or it was testing the calibration of my moral compass to see if it could stick, and somehow, I arrive at this moment where I feel “this is my moment” to just tell it as it is.