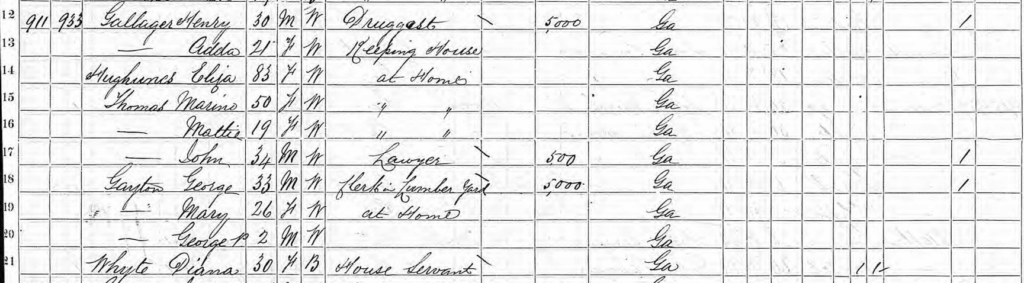

Where I started over two years ago in genealogy research and where I am now are two very different places. My skill set for this work has steadily progressed. Still, I catch myself in frustration when I try to locate evidence of my female ancestors. When I spent a month in August of 2024 in Savannah to do some archival research, I remember being struck by how hard it was to locate the women in my family, and when I did, certain names were misspelled from year to year in directories, newspapers, and court documents. The process starts by looking for male ancestors in a general document like a county census with the hope that the females will be listed with a first name. Women who are heads of households will often be confused as the wife of another male or some other relation if they aren’t the first name listed (as I found in the 1870 Census of Savannah below). In this census, names are mangled/misspelled, and the head of the household is not the Druggist, and the one “at home” is actually the owner of the property and head of household: my 4th great-grandmother Eliza Vallard Huguenin (EVH). To search for this particular census for Huguenins, Thomases, and Gadens would be hard to find if I didn’t know the names of Thomas siblings, who died relatively young, which I was not trying to find initially. In this census, Huguenin is spelled as “Hughunes,” Gaden is spelled as “Gayton,” and Malvina is spelled as “Marino.” In fact, when I first located this census record, I wasn’t sure I had located the Thomas family because of the distraction of Henry Gallager as head of household. I knew that Eliza Vallard Huguenin existed because I have her portrait in my Vault of items with an inscription on the back of the portrait written by my great-grandfather Marion Russell Thomas: “Eliza Valard Huguenin Grandmother of E. J. Thomas who is my father, Marion R. Thomas, Feb 2 1917”. While she is the grandmother of EJT, she is the mother of EJT’s mother Malvina Henrietta Huguenin Thomas. Malvina was one of three children of John and Eliza Vallard Huguenin (her siblings were Edward David Huguenin, 1806-1863; and Eugenia Amanda Huguenin Rose, who married a Hugh Rose in 1828. I am still searching for more information about Eugenia).

Without finding evidence that Eliza Vallard Huguenin was alive in 1870, I would not untangle much of the stories of my 2nd-great-grandfather’s siblings and other people who were living at that time. Until that point, the information I had about EVH was in a comprehensive biographical sketch from Nancy Birkheimer when she was a student at Armstrong State University taking a course in archival research. Most of the information provided by Birkheimer is very accurate, and for my family members interested in her life, I highly recommend reading the online biography here!

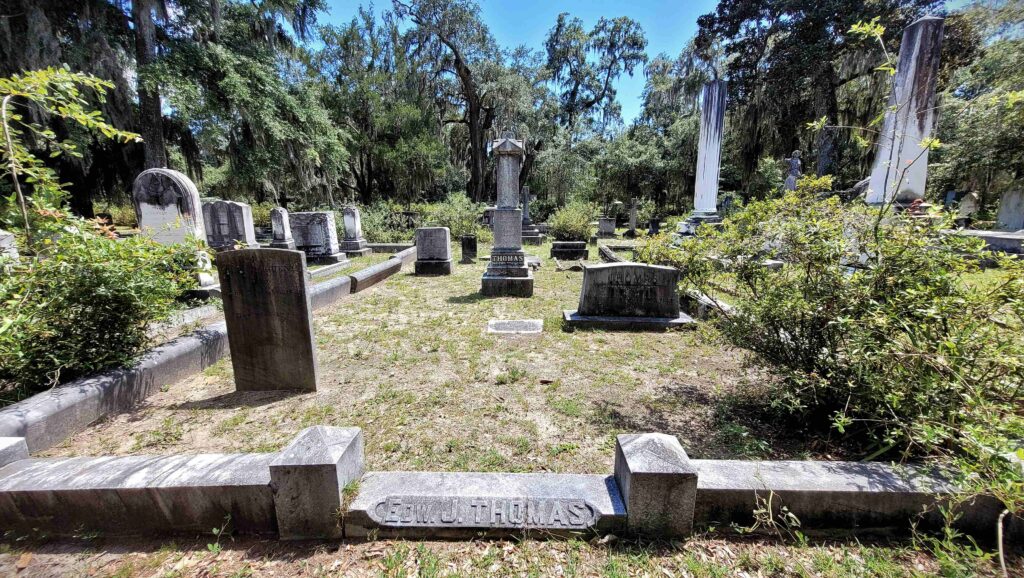

Eliza Vallard Huguenin was a woman who far outlived her husband, my 4th-great-grandfather John Huguenin. He died in 1835 and is buried in the Thomas plot in Bonaventure Cemetery. I cannot find Eliza in the cemetery as of this date, even though I have found her estate records detailing her funeral expenses, the type of coffin, and the nature in which it would be carried. EVH is the primary source of income for the entire Thomas family during/after the Civil War as she owns 1,400 acres of land south of Savannah and her substantial residence on Liberty Street.

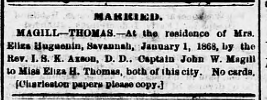

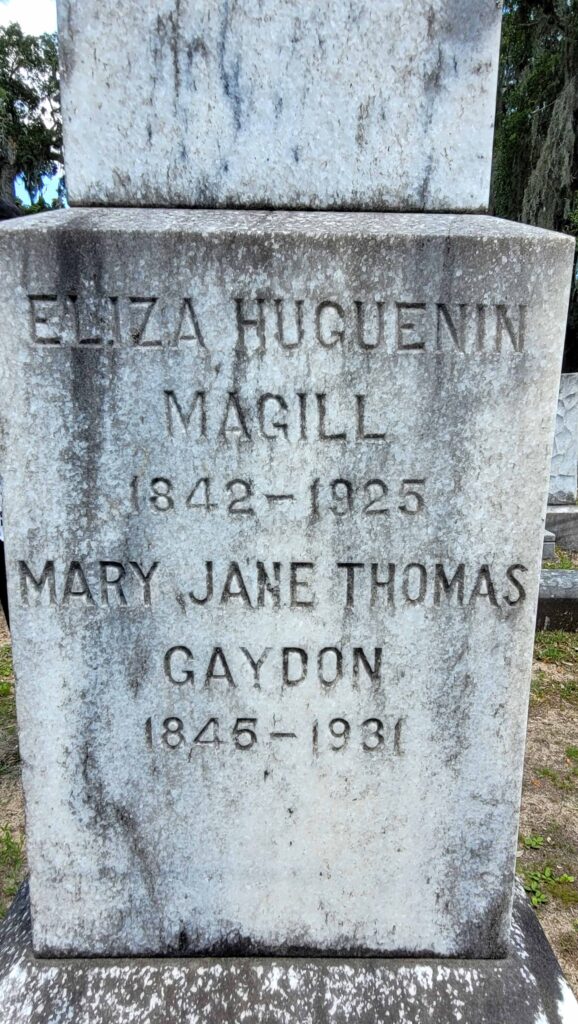

While searching for women in their single lives, I might find their names in court-documented marriage settlements drawn up prior to their wedding dates (signaling wealth), in newspaper notices (especially lists of letters held at the post offices in newspapers), in lists of rare schools, or listed in a city directory once they came of age. They did exist, of course, but they weren’t in the public domain as the men in their lives were. If a woman married, her name was often Mrs. [insert man’s name] for the remainder of her life, until a time when she became a widow or if she divorced. For example, my 2nd great-aunt Eliza Huguenin Thomas married John W. Magill on New Year’s Day in 1868 at the home of her grandmother Eliza Vallard Huguenin. This would be the last time we could witness her name “Miss Eliza H. Thomas” in public records.

After her marriage, she was Mrs. J. W. Magill or other variations of his name (except perhaps on a census record). Once I started seeing her name in the Savannah newspapers in 1884 as Mrs. E. H. Magill, I realized that she might be a widow. Widows took on new naming systems where middle initials represented their maiden middle names. Searching for a female “Thomas” can be particularly difficult (for example, Eliza would not go by Eliza Thomas Magill, or Eliza T. Magill). Naming systems for women are part of the decoding process in research. In the case of Eliza’s sister Mary Jane, she became Mrs. George T. Gaden, but after 1892, she went by Mrs. Mary J. Gaden or Mrs. M. J. Gaden.

Yet, almost everything I do have is because of the generosity of the women in my family. Edward Jonathan Thomas (EJT), my 2nd great-grandfather, had six siblings and his mother Malvina, who survived until 1890. I’ve had to lean into my Family Vault, including the memoirs I have found and the Family Bible. I also have a collection of letters from a “Cousin Rosa” that were written to my grandmother in the 1940s until my grandmother’s mom’s death in 1950. I mistook her for another Rosa for years until I found out she was the one daughter/only child of Eliza Huguenin Thomas Magill and John W. Magill.

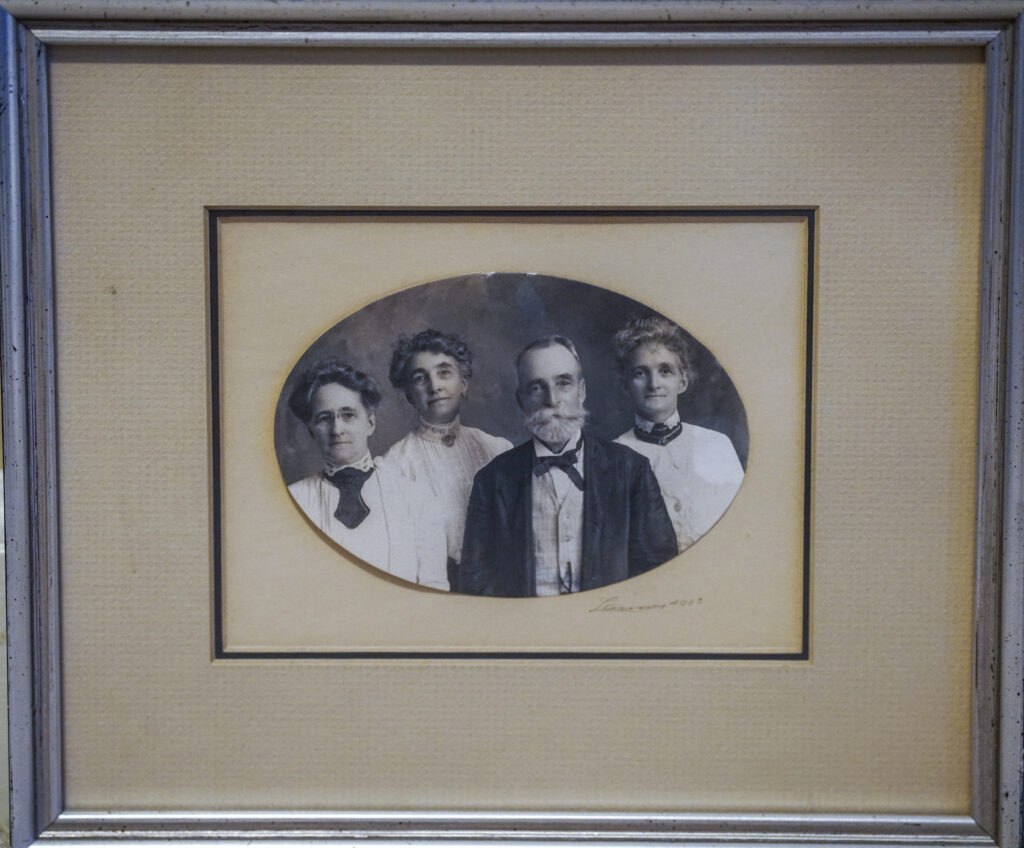

Photo by Arthur R. Launey of Savannah in 1901 or 1903, part of my personal archives. An interesting note about Launey: he was the father of Beatrice Cornelia Launey, who married Edward J. Thomas, Jr. This would explain why almost all the portraits I have of the family are from Launey as the photographer!

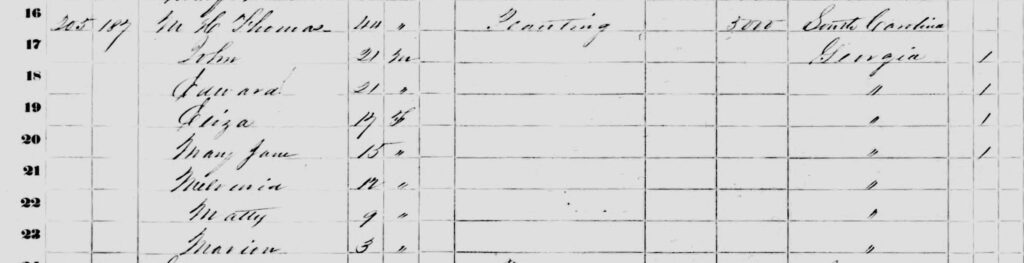

Of the six siblings of my 2nd great-grandfather Edward J. Thomas, four were women: Eliza (“Lila”) Huguenin Thomas (marries a John W. Magill, Canadian); Mary Jane Thomas Gaden (marries a George Thistle Gaden, Canadian); Malvina (“Mell”) Huguenin Thomas (never married); and Martha (“Mattie”) King Thomas (never married, died at the age of 28 in Darien, GA in 1879). There is a possible sister born approximately in 1857 named “Maria/on,” but I think the 1860 Census of Liberty County, where the Thomas family lived in Walthourville, has “Marion” confused with Houston Huguenin Thomas, who was born in 1858. But it is very possible there was an additional sister who died as an infant. However, Houstoun would have been in the census and is not — a mystery I will likely never solve.

Of that entire generation of siblings, the last to die was Mary Jane Thomas Gaden, who lived in Savannah at the time of her death in 1931. Her last name is forever memorialized and misspelled on her Tombstone in Bonaventure Cemetery as Mary Jane Thomas “Gaydon.”

There are a few possible reasons for this big error by one’s own family, but my best guess is that her nephew (my great-grandfather Dr. Marion Russell Thomas) didn’t know the spelling of her last name and used what he had in the Family Bible and what was on her death certificate for guidance as he reported her death. The family Bible also has Gaden spelled two ways: as “Gayden” in a handwritten note of her birth and death dates, and as “Gaydon” from a newspaper article from 1890 when her mother died. Her death certificate indicates she is “widowed,” but she did file for a divorce in 1892 in New York, something I suspected, but confirmed this past week. Her ex-husband would marry another woman months after their divorce.

Marriage would be one of the greatest risks to a woman’s future. Having witnessed the few marriage settlements as far back as the 1820s in my family, unless a settlement was drawn up, the woman who married followed the condition of her husband. If she didn’t bear children, her livelihood would also be at risk upon the death of her husband. If she remarried, after a husband died, she must create a legal document to protect the future of her and her children from a previous marriage or marriages. And if she divorced, which Mary Jane Thomas Gaden did, she better have a plan in mind.

As such, I’d like to focus a bit on my 3rd great-grandmother (Malvina Henrietta Huguenin Thomas-MHTSr.).

In 1859, her husband John Joel Abbott Thomas (JAT) died from a brain injury he sustained after being thrown from a buggy while riding with his son Edward Jonathan Thomas (source: EJT 1890-1923 Memoir in the Georgia Historical Society). Malvina would have seven children to care for at this time, her oldest being John Huguenin Thomas (JHT), then Edward Jonathan Thomas (EJT), both of whom were attending UGA and scheduled to graduate in 1860. JHT is 20 and EJT is 19 at the time of their father’s death. The other children are aged from 1 to 17 years old. Their wealth was undisputable as JAT inherited his father’s, Jonathan Thomas’s, lands in McIntosh County, but with the family living in Walthourville because of the availability of schools, Malvina relies on the family attorney/estate trustee and direct neighbor William J. King in McIntosh County to manage the properties in McIntosh County. JAT’s father, Jonathan Thomas (JT) died in 1845, and the evidence of his estate administration to his son JAT is scant in McIntosh County; another generation handled those estate matters I suspect because Malvina Huguenin Thomas did not have a will in hand or could not process the estate as administratrix. When JT died, his second wife, Mary Ann Williamson Houstoun Thomas was also a woman in possession of many properties in McIntosh and Chatham counties. Their marriage settlement before marriage would protect her and her children from a previous marriage after his death, but his holdings (Lowe, Stark, and Peru tracts in McIntosh County) would go, eventually, to the widow of John Joel Abbott Thomas (Malvina) and their seven children.

EJT recounts that after his father’s death, he and his brother John Huguenin “Hue” went back to UGA, and his eldest sisters Eliza and Mary Jane went to boarding schools (one in Philadelphia, PA, and the other in Montpilier, GA, where no records exist so far). EJT and JHT would graduate from UGA in 1860, and JHT spent another year at Lumpkin Law School at UGA to become a lawyer in 1861. Left at home with Malvina Sr. in Walthourville, then, are Malvina Huguenin Thomas Jr (MHTJr), Mattie King Thomas, and Houstoun Huguenin Thomas. By 1870, everyone will be in different places from McIntosh County to Chatham County. During the Civil War, Malvina is tasked with the care of the younger children while John and Edward served in the Confederate States Army (CSA). Malvina must have had to rely on her mother, Eliza Vallard Huguenin (EVH). Malvina’s daughters Eliza and Mary Jane went to Limestone Springs, SC during the Civil War to stay at Limestone Springs Academy where their new sister-in-law Alice Gertrude Walthour Thomas (AGWT) had just graduated and whose oldest sister Eliza Amanda Walthour Curtis lived with her husband Rev. William E. Curtis (the co-founder of the school).

Malvina must have had to juggle quite a bit as a widow between 1860 and 1870. The lands of Jonathan Thomas (Lowe, Stark, Peru Tracts) in McIntosh County were divided in about 1873, years after the Civil War. At the same time, Malvina tried to settle her mother and father’s property in Chatham County (about 1,400 acres 7 miles south of Savannah in Bethesda area and the city home in Savannah on Liberty Street) after 1870 when her mother Eliza Vallard Huguenin died. At one point, she is named the executrix of her father’s estate, and she, along with the survivors of her brother’s estate (she is the lone surviving child of the Huguenin siblings in 1871), successfully challenge her own mother’s will because it attempts to leave all her estate to her oldest son John Huguenin Thomas. It gets very, very messy, and it takes years to settle this estate. Between 1859 and the 1880s, it is Malvina who is the full or partial heir to many of these lands/properties, but her sons and brother are the ones who orchestrated the land negotiations. I can’t help but wonder what land disputes would have looked like had women been the ones to advocate for themselves in these cases. Time after time, women outlived men, and they were beholden to male disputes and laws, even among the family members.

One clear thing is that Malvina takes equal portions of land with her children, not full portions, and as a result, the Thomas family retains their land and wealth. I imagine her as a force to be reckoned with (as was her mother—Eliza Vallard Huguenin—she is detailed in EJT’s memoirs as a stickler for rules and customs). Widows abound on many sides of my family, even on my grandfather’s side, and when they are left without the laws to protect them, they are vulnerable.

I know that this post is confusing and not linear. I haven’t even given the full timeline of anyone! However, it mimics my own discovery of these lives; I find surprise documents here and there, and then I circle back to my existing Vault and family Bible to see if I “missed” something, and inevitably, I do. My next posts will attempt to elaborate on two 2nd great-aunts specifically in order to illuminate the Thomas family beyond the patriarchal arch of history, including the elusive life of my great-great grandmother Alice Gertrude Walthour Thomas.